Building the Vimy:

Part III: It All Comes Together

by Miles McCallum

On top of all that original creation, the target deadline

was 12 months from the start of construction. Peter was

determined to re-create one of the great Vimy record setting

flights — England to Australia — on the 75th anniversary

of that flight. Romantics have a thing about anniversaries...

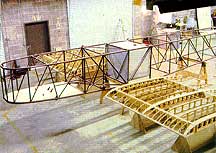

By June, the forward fuselage and PSRUs were completed

in Australia. By then, sponsorship and assistance (some

of it the sort that no amount of money can buy) started

coming in from diverse sources such as the RAF museum

and Brooklands on one hand, and Stanford University on

the other.

Component

pieces came together fairly rapidly. All spars completed

by July. Lower wings at the end of August. The center

section a month later. By the time the rear fuselage was

complete and shipped from Australia in October, the wings

were complete. In November, the tail was completed, testing

started on the engines and PSRU gearboxes, and National

Geographic was signed as major sponsor for the Australian

flight. Component

pieces came together fairly rapidly. All spars completed

by July. Lower wings at the end of August. The center

section a month later. By the time the rear fuselage was

complete and shipped from Australia in October, the wings

were complete. In November, the tail was completed, testing

started on the engines and PSRU gearboxes, and National

Geographic was signed as major sponsor for the Australian

flight.

In the interests of an accurate finish as possible, it

was decided to cover the aeroplane exactly as it had been

74 years before, using grade A cotton. With a thread count

of about 90/inch as opposed to 50-odd/inch, the difference

is instantly recognisable to those with an eye for historical

accuracy. In addition, they decided to apply the dope

by brush. This leaves a characteristic signature to the

finish, as well as being a lot less hassle to apply.

In December '93, the master fabric team from AJD Engineering

in the UK came over for 10 days to instruct the American

fabric crew in the use of natural fabrics — there is little

experience of cotton or linen in the USA.

The tally of covering materials left even John amazed.

"Five hundred yards! [of aircraft quality Grade A cotton]

WOW!" Coming in 5ft wide, 100yd bolts, it had to be sewn

into blankets for various components. The wing center

section, for instance, took five x 22ft long pieces sewn

edge to edge. Giant "rotisseries" had to be constructed

to handle the outsized pieces. The fabric was draped over

each piece, trimmed, and glued at the edges before being

shrunk with distilled water. Final tautening was accomplished

using Nitrocellulose dope as per the original.

Rib

stitching was the last great dreary task. Over 10,000

knots had to be tied in total and the first wing panel

— needing about 1000 knots — took several days. With practice,

that came down to 12 hours a panel with three or four

people, at the rate of three hours per rib of 84 knots. Rib

stitching was the last great dreary task. Over 10,000

knots had to be tied in total and the first wing panel

— needing about 1000 knots — took several days. With practice,

that came down to 12 hours a panel with three or four

people, at the rate of three hours per rib of 84 knots.

The surface tapes, covering the rib stitching and reinforcing

critical areas, had to be right. Modern surface tapes

usually have a pinked (zig-zag) edge, whereas in 1919,

they used frayed tapes. These are made by ripping cotton

into strips, and stripping a couple of the warp threads

from the edges, leaving the characteristic frayed edge.

In effect, they work exactly like pinked edges. Nearly

a mile of tapes were ripped, frayed, ironed and hung over

several weeks, before being doped on, followed by a further

three coats of Nitrocellulose.

In the interests of safety, being much less incendiary,

the two silver (ultraviolet barrier) and green finishing

coats of dope were Butyrate. The colour of the finish

coats was matched to a piece of the original fabric from

G-EAOU — the entire left aft fuselage cover. The covering

job took four months alone.

Rigging the wings for the first time proved to be a case

of making it up as they went along. Rather than assemble

it as Vickers did 75 years before — by starting with the

lower center section and working up — they completed the

lower panels, and then fitted the top wing, including

ailerons, in one go. This presents something of a problem

when you are dealing with a flimsy 68ft structure weighing

1000lb needing to be accurately positioned 16ft up. The

strength is developed once it has been tied into a rigid

box structure with the rigging wires.

The components were moved to a huge hangar in Hamilton

Airforce base at Novoto, California, and a giant truss

built to support the top wing while it was hoisted into

position. Bracing wires were provided by Bruntons of Musselburgh,

the Scots company that had provided the wires for the

original Vimy.

This time, in the interests of better safety margins,

the flying wires (those that go up and outboard) were

doubled up. No one had any experience of such a large

biplane, and a fair amount of trial and error was required

to complete the job.

© Miles McCallum 1997, 1998.

Photos by Matthew Rebholz show the Vimy under construction.

|